After the Beatles were on Ed Sullivan, everyone was getting a guitar. My father, who was quite certain

that conformity was "the hobgoblin of lesser minds," decided that I was going to play something else. So I ended up with a tenor

saxophone. This was more or less OK since the next week the Ed Sullivan Show featured another English rock band called the Dave

Clark Five.

They were essentially a shameless rip-off of the Beatles except that they had a fifth guy on saxophone. Their hit song "Can't You

See That She's Mine" had a three note saxophone solo, which to my delight I was able to master in about fifteen minutes. I was

sure that fame could not be far off.

I had pretty good luck in the Bedford Junior High Music Class. We were allowed to bring in our instruments and play for the class.

I had moved on from the Dave Clark Five to the theme song from Peter Gunn.

The teacher laughed out loud at my outrageous attempts to gyrate and bend razzing blues notes out of my saxophone. Blythe, a girl

in the music class who had played "Kum Ba Yah" on her nylon-string guitar didn't seem overly impressed either.

However "Louie The Shark Nistico," over-seer and protector of seventh grade coolness, loved it. Louie had a Rogers sparkle-blue

drum set. He could play "Hold On, I'm Comin'" just like on the record and he had a band. I was in. Life in Louie's band was not all

I had hoped for. I was issued a v-neck, satin, rose colored shirt and relegated to a line of horn players who played dah-duh-dah

dah on the off beat while doing a rudimentary dance step on the beat. At the end of the year the Town announced that they would be

opening a third Junior High in Westport, named Coleytown.

I would be transferring there and Louie and I would be separated by a geographic chasm, which would require a driver's license to

bridge. Thus ended my brief career in Motown-style music.

My teenage rebellion consisted of devoting an increasing amount of my extra-curricular time to the guitar.

The hours Jeff Dowd and I used to spend together on the split rail fence in his backyard, emulating the "fall dead" stunts we

observed on Davy Crockett, were replaced with Jeff passing along precious tips from his guitar lessons to me. We would also sit in

his father's art studio, me at the upright piano, Jeff with guitar in hand, figuring out the intricate harmonies of Lennon and

McCartney. Another friend I had met in church proved to be a musical influence, too.

"Hey, Boy-sea-oh," I would yell out across the play yard. My friend would look down with scorn. "Buuuhwaaahhhsooooooooo," he used

to proclaim with a flourish to those whose French accent he found lacking. One day I visited the home of this fellow guitar

enthusiast, Chuck Boisseau. His older brother, John, was the ultimate role model for coolness. He was constantly trying to repair

his motorcycle in the driveway, wearing a leather jacket (so that he would be ready, in case he ever got it started) while

beautiful blonde girls would stand by and watch with undying admiration. John also played a black hollow body Epiphone guitar. He

didn't listen to 45 rpms. He had LPs. One of them was called The Paul Butterfield Blues Band. I wasn't completely sure what to make

of it. The album cover showed a mixture of Black people, White people, Hippies and Greasers standing together in front of a rundown

storefront and acting as if they got along with each other! This was a totally new concept for me. What I did figure out right away

was that the guy on lead guitar, Mike Bloomfield, had it all over George Harrison.

I was blown away by what I had heard and immediately stopped listening to Top 40 radio stations such as WABC with Cousin Brucie...

and the WMCA "good guys".It was becoming fashionable at that time to reject the bubble gum music that was being played on AM radio

such as "Yummy, Yummy, Yummy, I've Got Love In My Tummy" and focus on more intellectual songs featured on long playing albums, such

as "Inna Gadda Da Vidda (Baby)." I started hanging out at the record counter at Klein's department store in downtown Westport where

I learned underground music lingo.

Based on my collection of microphones from a military surplus store I was invited to join a garage band with my neighbor Jeff Dowd.

Garage band is sort of a polite term for a band that isn't really good enough to get any gigs. This band consisted of Jeff's school

chums from Assumption School. Robby McClenathan had decent chops for playing bass, but he didn't own a bass so he would tune down

the bottom four strings on a regular guitar until it was inaudible. And Danny O'Grady would get really defensive if you asked him

to play the drum part on "Fire" by Jimi Hendrix. Things looked pretty bleak. In addition I was working at the grocery store

stocking dog food.

Then Chuck Boisseau quit his band "Smoke" to concentrate on French horn and corporate law. The remaining members of "Smoke" debated

as to whether they should invite Jeff Dowd or me to replace Chuck. One amongst them suggested, "Why not both?" I was out of the dog

food business for good. We were having fun and learning rules of life that all sixteen year olds should learn:

1. The engine of a 1957 station wagon will seize if you try to drive it up a hill 90 miles an hour loaded with drums and

amplifiers.

2. Never let a band member who has had 23 beers play their trombone in public.

3. Paraphrasing tenor saxophone solos from John Coltrane's "A Love Supreme" doesn't particularly work as an instrumental break for

"Hang on Sloopy."

Despite these occasional lapses, we were a "jacket and tie" band, which meant our hair wasn't too long and our clothes weren't too

outrageous. So we could get hired by Republicans to play at the Country Club.

We also played a lot of proms, which meant that we didn't have to go to them. Proms were in a state of transition in the late 60s.

They definitely were part of "the establishment" so if you were part of the Woodstock generation, proms were somewhat "out of it."

But somehow not having a date for the prom didn't seem very cool either; so playing in the rock band that was hired for the prom

seemed like the ideal solution.

Jeff was the lead guitarist and I did a certain amount of 2nd guitar as well as flute or saxophone (usually tenor, although I

played baritone and soprano as well). I learned my first lessons in arranging in those days. We recruited Peter Cody and Herb

Whitely to play trumpets and Andy Kautinz and Dan Potter on trombones. For those four horns plus myself on tenor sax, I made 5-part

arrangements of songs by Sly and the Family Stone, Wilson Pickett and Blood Sweat and Tears. We also burned the midnight oil one

weekend, with John Leimsieder leading the way, figuring out chord changes and riffs in order to present a huge chunk of the Beatles

Abbey Road at a gig before most people had even heard it.

There were several good, hell, great bands playing around Westport in those days. The Soul Purpose, Styx, Mandrake Root, Rector

Justin, and Smoke. As famous bands such as the Beatles and Cream started to disband, so did our local bands. The novelty of playing

in a cover band wore off. As with all things that are self-governed by a group of testosterone-poisoned 17 year olds, there were

differences of opinions and I departed the band. Mike Mugrage replaced me, and the band played on briefly. I had heard enough great

lead guitar players from these other bands such as Charlie Carp, Tony Prior, Chuck Boisseau, and our own Jeff Dowd to realize that

I was better off concentrating on sax. So I used some of my rock earnings to buy the most beautiful Selmer Mark 6 alto sax ever

fashioned by human hands. My record purchases also took a sharp left turn.

I bought Ornette Coleman's "The Shape of Jazz to Come" which was weird, weirder and weirdest. Now I was jamming with Chris Tolkien,

Hank Anderson and Gary Pare. We were learning jazz and discovering that its complexities were light years away from the naive and

simple joys of playing Rock and Roll. That ensemble wisely opted to limit its public appearances. I started cramming classical

saxophone etudes for the impending college auditions for which I was woefully ill-prepared.

Even after Smoke was declared more or less dead, at least as an organization that held regular rehearsals, booking requests for

Smoke would still come through to John Leimseider's mother (who had been the closest thing we had to a business manager). After a

round of consultation, various members of the band who were willing and available would play that particular gig. I did play one

such gig with John and Tom. As I recall we were only able to play a very small number of the songs from the band's original list

(since there were only three of us) but each song lasted about 14 minutes, which got us through the evening. This occurred (not

coincidentally) at about the same time as many famous bands were releasing their "LIVE" albums, which also had 14-minute renditions

of songs that had originally been 2 minutes and 30 seconds on the original album. I'm not sure it was much of an improvement in

either case.

After graduating from Staples I ended up at the Kansas City Conservatory where my saxophone teacher Charlie Daugherty must have

spent most of my lesson time formulating a way in his mind to break the news gently to me that I was not ever going to catch up to

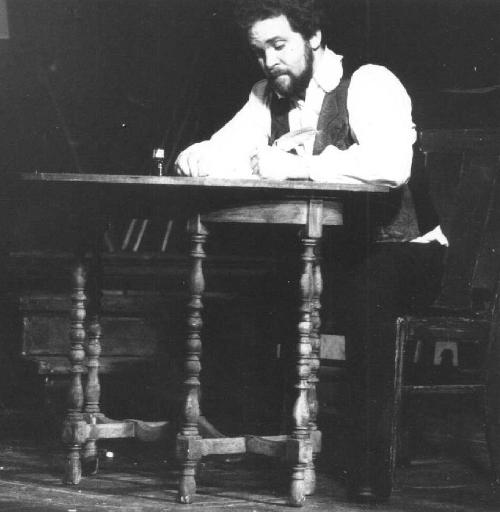

Charlie Parker. I went to the Kansas City Lyric Opera one night where my voice teacher was scheduled to perform the leading role

in Pagliacci. All of the operas were sung in English so there was no advanced preparation required. I sat in the darkened theater

and watched the performance of Pagliacci unfold. Passion, treachery, betrayal. "The comedy has ended (La commedia è finita)".

That was it for me. My life had attained purpose. But how would I get up to speed? I deserted the saxophone. My new found zeal

landed me the role of Dr. Cajus in the Conservatory's production of Verdi's Falstaff. That February I brought the entry form for

the regional Met auditions to my voice lesson. You have to have your teacher sign the form. My teacher, Richard Knoll, shrugged his

shoulders as he signed and reminded me that most of the advanced singers in the school would be participating in this contest. To

my total shock and amazement I was one of the three winners at the regional level. That was all the encouragement I needed. After

completing my Bachelors degree, I attended Indiana University for two years where I majored in Opera, Food Service and Pinball. In

1977 I arrived in Hartford to attend Hartt School of Music where I (finally) finished my Masters degree in 1979. I met my wife

Ginna in Maine that summer. In the fall she was starting Graduate School at the University of Washington in Seattle. So I pulled up

stakes and headed west. Seattle Opera was at the height of its obsession with Wagners "Ring des Nibelungen". I was lucky enough to

procure an apprenticeship with the Opera Company.

I have performed with them as a soloist and chorister for 23 seasons. I have also performed with the Seattle Chamber Singers as

tenor soloist since 1985. I have been a guest soloist with The Seattle Symphony as well as other West Coast symphonies and opera

companies. In 1989 I toured Japan with The Sapporo Symphony in Händel's "Messiah." I taught voice at Pacific Lutheran

University for 16 years before retreating to the sanity of a studio at home. My students are beginning to get work as soloists and

win grants in major music competitions in our area. Ginna and I will have our 25th wedding anniversary on October 2nd, 2005. We

have two children.