Forza Italia!

A Zeffirelli polemic in five acts and a prologue

|

Franco Zeffirelli has lately

made headlines all over the world. In connection with his new [this article was written in 2007] production of

Aida at La Scala, he attacked many of his stage director colleagues and the

"modern" stage design in general (whatever that is). Zeffirelli resorted

– probably deliberately – to using a verbal sledgehammer and a style which is normally

used by gutter papers, yellow journals and the like. Here is a

sampler: "We should all be very proud of tonight because it returns melodrama

and Italian opera to the top class after so many abuses that the Germans and

English and so-called colleagues have done to our heritage." (Reuters)

In an interview with the Corriere della Sera, Zeffirelli said that his aim was

saving Italian opera from "criminal" foreign directors who corrupt

the art by tampering with the librettos and the staging of works: "If we

don't take shelter against such barbarity, our children won't even know what

opera is." (Reuters)

His Aida at La Scala was, according to Zeffirelli, meant to be a manifestation

of what "one can do with opera" and a demonstration against "the modernizations

that are common in Northern Europe and that are contrary to the nature of

opera. In the 19th century, opera was the heart of Italian

culture (...). And that is why we have to defend our roots. We can't just throw

them away because some new aesthetical movement from the north wants to tell us

how to treat them." (Il Giornale) And so on

and so on. What is hidden behind all these grandiose words is one simple

message: "I know how to stage Italian opera." Zeffirelli refers to the

traditions of the 19th century, the heart of Italian culture of

which he thinks is a, maybe the agent. And, of course, the defender of

Italian culture against the barbarians from the north: once again, the Italians

have to deal with the invasion of the Teutons, and, alas, also Anglo-Saxons and

other criminal foreigners. But we should not resent Zeffirelli's choice of

words. Zeffirelli has always been a friend of a rather ribald choice of words. Back

in 1991 he insulted the "Arab culture" (whatever that is) as "barbaric,

primitive and violent" and accused the Islam of having caused "more damage than

the Nazis". Being a

member of the right-wing extremist party Forza Italia, he has also frequently

denigrated the political opposition with similar words. But back to opera. Is

Zeffirelli the advocate of the 19th century tradition? Is his anger

really motivated by the defence of Italian culture against Nordic barbarians or

is his Rambo attitude motivated by political resentments? Only a look at his

work will give the answer. |

Otello

|

Otello opens

with an "Allegro agitato" and a diminished C major seventh chord, including d and f

(clarinets and horns) – a beautiful and almost complete unfolding of C Major.

Franco Zeffirelli provides the pictures that accompany the music: a

relief that shows the Venetian lion, flashing in lightning and thunder, a

veritable storm, heavy rain and a schooner that struggles with the breakers of

a furious sea. We see a crowd in medieval costumes, concerned about the welfare

of its leader. We see Desdemona, squirming with fear; her blond hair, wet

from the rain, sticks to her face and her mouth is half open. A frightened

crowd prays in a little chapel in front of a huge crucifix that is illuminated

by countless candles. The crowd sings and screams, speaks and declaims. Otello

appears in a virile pose, and with martial expression he sings the heroic

"Esultate", while the rain is lashing on his face. His skin has a pleasant dark

colour, and his lips are red. Desdemona, speechless from joy and relief, laughs

and runs to meet Otello. In a short moment, we see Iago, making a grim face

with the flames of a campfire in the background. Otello kneels in front of Desdemona

and presents his sword. Amidst the cheering crowd she kisses the hilt

and then Otello, long and passionately.

That is how

Zeffirelli presents the opening scene of Otello in his famous opera movie with

Plácido Domingo as Otello and Katia Ricciarelli as Desdemona. The first

sight is, like in most Zeffirelli movies and productions, impressive,

downright overwhelming. The colours of the set are perfectly harmonised, the

costumes attest greatest accuracy, and the set testifies to unusual care for

the detail. The set wants, no doubt, to give a "realistic" impression. That is

the reason why for example the crowd screams and declaims in addition to the

singing. The camera takes multiple perspectives. Zeffirelli's accuracy aims

at creating a realistic picture, which he understands as the only way of staging

opera – not only on screen, but also on stage. And for Zeffirelli, the

concepts of "realism" and "traditionalism" are closely connected. He claims

that a "realistic" looking stage, a detailed one with the "historically

correct" costumes and sets is "traditional", because it is what the composers

originally wanted. That means: what we see on the screen of the Otello movie is

"traditional" because it is "realistic" – because, according to Zeffirelli,

Verdi wanted it as accurate, as "real" as possible. Fidelity in the composer

and, as he says, the tradition of the 19th century and the heart of

Italian culture, is the keyword. "Traditional" is "realistic" – "modern" is

something else.

In spite of

the fact that such statements ("I do what Verdi wanted") are impossible to

verify, Zeffirelli has to put up with a couple of critical questions. Of

course, Zeffirelli has understood (without admitting it) that opera is a

totally unrealistic medium. Nobody in real life sings, and that is why he made

the crowd speak. The opera was to become more realistic, as also the multiple

camera perspectives betray. Zeffirelli shows as a real thunderstorm, a huge ship

and the crowd in different places (inside a chapel and outside). Those

things were never realizable on any opera stage. Verdi was, however, a man of

the theatre. Cinema did not exist in his time. Verdi's visual aesthetics are

theatre aesthetics. So how can Zeffirelli say that what he put on the silver

screen is what Verdi wanted? Zeffirelli shows singers or actors who do not sing

and who just move their mouths lip-synching. That is for sure not what Verdi

wanted. Then he shows a Spanish tenor with brown paint in his face and with lips so

red that they could make any Desdemona green with envy. Domingo does not look

like a moor – he looks what an Italian director believes a moor to look

like. Zeffirelli presents a medieval scene where everything is pretty,

delicious and clean. His aesthetics are purely Apollonian; he creates a world

in which everything ugly is banned. So is the photography: blurry in order to

make the few remaining edges even softer, in the tradition of Visconti's

movies from the 1970s.

If

Zeffirelli wants to stage an opera the way that Verdi wanted it, why doesn't he

do the same with the music? What he presents is a recording

characterized by the miracles of electronics. First of all, the opening music is not

in the right key, it is not C major. The whole opening scene is lowered by a half

note, and that's how Domingo sings the "Esultate" – perhaps so as to make his voice sound

darker and more virile? Comparing the recording to a live recording with the

same singer, the difference in timbre is stunning. In the film version,

Domingo sounds unusually dark and dramatic – an effect which was not only

achieved by transposing the score but also by manipulating the voice. That is

what Verdi wanted?

The sound

aesthetics of Zeffirelli are totally modern. The singers sound like singers of

today, not like the singers from Verdi's time. Zeffirelli is utterly

inconsequent: He wants a stage "like Verdi wanted it", but he does not care

about the music. If he were consequent, he would look for singers who sound

like Tamagno, but that might prove difficult. He furthermore rearranged Boito's

libretto and made cuts in Verdi's original score – about 30 minutes are

missing. Still, he claims that he is one of the last directors who are

"traditional" and close to what the composers wanted. The one who will save opera

from "'criminal' foreign directors who corrupt the art by tampering with the

librettos"!

ESULTATE

from the manipulated movie score, followed by an ugly cut –

a digest version for people

who do not have enough patience to listen to the entire opera.

ESULTATE

with Domingo from a 1976 live performance under Carlos Kleiber –

a real musician who would

neither allow to change the original key nor to make cuts in the score.

ESULTATE by Francesco Tamagno – Verdi's

choice for the role of Otello.

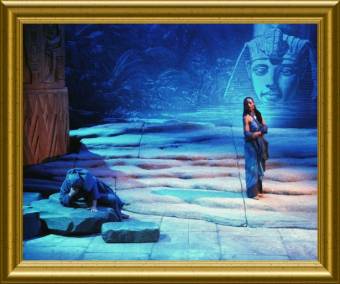

Aida

Aida is

Zeffirelli's favourite opera, "the opera of my life", and he has created sets

for it for many stages. The Aida sets that he has created (above a

mise-en-scène in Busseto) have been similar to the style of the Otello movie

and other sets by Zeffirelli. But Aida is an opera that is impossible to

stage "historically correct": no "realism" can overcome the incredibility

of the libretto. The plot, invented by Auguste Mariette-Bey, is not based on

any kind of historical source and is full of mistakes. A few examples: The action

takes first place in Memphis, then in Thebes – as if the distance of over 620

kilometres between the two places did not exist. Even worse is the distance between Thebes

and Napata ("di Napata le gole"), which is to be found in Sudan. A travel from

Thebes to Napata would have taken three months and not one day.

In old Egypt, consecration of a commander (Radamès) did not exist, and it was

not the oracle that appointed the commander. Egypt was no theocracy as shown in

Aida. The tomb scene would have been impossible in old Egypt, as death penalty

in the form of getting buried alive was not practised. A Liebestod for which

Wagner's Tristan was the inspiration and not the history of old Egypt. The

names of the protagonists are mostly fantasy. A name like Aida or Aita

did not exist in old Egypt. Dieter Arnold found out that one of the

girlfriends of Ismail Pasha (the sponsor behind Aida) was called Aida. But that

was an Arabian name and had nothing to do with Egypt.

Amonasro (Amounasro, King of Meroe 260–250 BC) is the only authentic

personal name in the libretto. The whole opera is, as Jan Assmann rightly

put it, "an Egyptologist's dream"

– nothing less, but also nothing more.

Aida cannot be staged

"historically correct" or "realistic" as the libretto is ahistorical and

unrealistic. Of course it seems legitimate to re-create the atmosphere in which

Aida was presented for the first time, the exciting history around the genesis

of the opera, the interesting meeting of Western modernization and Egyptian

national romanticism. Such a staging would always include all the pomp, the

gaudiness of the first performance. Zeffirelli comes most probably close to the

original, at least in this regard. The problem is that Zeffirelli often reverts

to the typical souvenirs of Egyptian culture (see picture) and puts together a

stage set that does not look like "an Egyptologist's day dream", but like

an Italian who has never been there imagines Egypt. When

Zeffirelli uses hieroglyphs, they don't make any sense. The architecture he

presents does not have much to do with the architecture of old Egypt. We have

the same problem as in Otello: the aim is realism, but the sets are

much too kitschy for being realistic. And in the case of Aida, Zeffirelli is in a

double dilemma, as also the plot is totally unrealistic.

If Zeffirelli fills the stage

with kitsch, he departs from what Verdi wanted, because the stage sets of the

first performance of Aida in Cairo were exact copies of historical

originals.

But why should it in the first place be desirable to copy the Cairo world premiere

anyway, or to copy "what Verdi

wanted" over and over again? If Aida performances on

all stages would look more or less the same ("historically correct" or kitschy)

for all times – why would one go and see it? Theatre lives because of the

frequent re-interpretation of old works, and not because of good copies of their

first performance. It is as Heinrich Heine said: "The first man who compared a

woman to a flower was a genius; all those who imitated him were donkeys."

Turandot

& Co.

The Metropolitan Opera House has

cooperated with Zeffirelli for many seasons. Stage design à la Zeffirelli is popular

in the US as also many creations of Otto Schenk prove. In 1983, Zeffirelli

staged Turandot at the Met. It can be seen on DVD, with Plácido

Domingo as Calaf and Eva Marton as Turandot. Again, we have beautiful costumes

and a set that tries to look as realistic as possible. We see China through

the eyes of an Italian, with all the elements of kitsch that will appear in such a

combination. That was certainly not too far from Puccini's own intentions

and the exotism of the time. So far so good. The problem with that production

is, however, typical for Zeffirelli. Like in Otello and Aida, Zeffirelli

focuses on the beautiful aspects of set and plot, and that's it. Zeffirelli's

approach to opera is extremely superficial. The sets and costumes for Turandot

are nice, the kitsch is dead on (albeit most probably unintentionally), but the

interesting story is ignored. Nothing of the libretto's subtext can be

seen in Zeffirelli's production. Puccini's Turandot is an exotic fairy tale, in

which Puccini presented the problems, the cultural crisis of Italy and Europe

in the 1920s – in a plot that takes place in the Far East. The libretto of

Turandot contains elements of both traditional poetry and expressionism;

the music plays with melodies in the traditional style of the Italian opera as

well as with dissonance and atonality. Liù is a character that expresses herself in traditional

poetry and melodic music. Turandot does not. Turandot does not sing rimes,

and she is not sympathetic. What about Liù, the sympathetic figure of

identification as a symbol of old, harmonic style and Turandot as a symbol of a

cold, ruthless future? (Post-WWII composers used the opposite effect:

traditional harmonics as a symbol for the bourgeoisie and the old currupt world

– dodecaphony for the a new free world with no bourgeoisie.)

What about Turandot's bloodthirsty crowd, the incredible cruelty of the first

act that stands for the modern times? What about the sarcastic animadversion on

the growing bureaucracy and hypocrisy in act two? That a cold

Calaf sacrifices the sympathetic Liù and marries an even colder Turandot is

not a happy ending, it's a dystopy. It is appropriate that Puccini (and with

him the old tradition) died after he had written Liù's last lines.

Zeffirelli's Turandot is

beautiful but superficial and hence certainly not "what Puccini wanted".

Zeffirelli's creations try to be "realistic" and "traditional", but they are

kitschy and superficial because they ignore the subtleties of the libretti and

focus on nothing but a glossy surface.

Another case is Zeffirelli's

movie version of Puccini's La bohème. It is a beautiful production, no doubt, maybe one

of Zeffirelli's best achievements. Even the musical performance with Raimondi,

Freni and Karajan is nice. But the total disregard for the bad quality of the

libretto causes a major problem. I would like to put it in the words of a

friend: "I've got Zeffirelli's Bohème, the music is very nice, but I still cannot

look at it as the story is so ridiculous." Zeffirelli did not care about the

quality of the libretto – but how could a director not care about the

screenplay? A good director makes a great movie out of a poor screenplay, and a

bad director can make a bad movie out of the best screenplay. Zeffirelli made

no attempt to turn the bad screenplay into something better, which is evidence

of incapacity. Zeffirelli's respect for the "tradition"

paralyses him. A bad libretto like La bohème needs originality and wit. The

productions of Rossini's Comte Ory by Savary and Tofolutti (Glyndebourne 1997)

or La belle Hélène by Laurent Pelly (Paris 2000) show how opera can be staged with

esprit. Aki Kaurismäki shot a wonderful and disrespectful Bohème in 1992

in which Rodolfo, here a poor painter from Albania, steels flowers for Mimì on

a cemetery. The tomb that he takes the flowers from is the one of Henri

Murger. Kaurismäki's Bohème is never boring. It is a true piece of art.

Kitsch

„...denn Armut ist ein großer Glanz aus Innen"

(„...because poverty is

great splendour from within")

RAINER MARIA RILKE

The great German encyclopaedia

"Brockhaus" (2001) uses three photographs in order to illustrate the term

Kitsch: a picture of typical German garden gnomes, one of a sculpture by Jeff

Koons of himself and Mrs. Staller and – one of a Aida performance directed by

Zeffirelli. And rightly

so, because Zeffirelli is, as Giovanni Bogani put it, indeed "a virtuoso in the

art of Kitsch". His Otello

movie is an unrivalled masterpiece in this regard. We just need to

remember Otello's makeup and the fact that Otello does not look like a moor but

what Zeffirelli thinks a moor looks like (which is, excuse me, more like a Klingon).

Why did he not employ a black actor – like Oliver Parker did – as the opera movie

worked with lip-sync anyway? He did the same kitschy faux pas in his filmed

version of the bible in which Jesus' turquoise blue eyes are particularly

captivating (and make him look like a devotional article).

Desdemona is, of course, a blond angel full of goodness and innocence and

hence always surrounded by an aura of light beside the rough and dark Otello.

The evil Jago is shown making a grim face with flames in the background. He wears of

course a beard in order to hide his bad character. The storm in

the opening scene is so exaggerated that, as Vincent Canby pointed out, "the

chorus of Cypriots – standing on the quay awaiting the arrival of Otello's

ship, their mouths wide open in rousing song – might well be expected to fill

up with water in a minute, as if they were bailing buckets."

(Canby also found Ricciarelli so blond that she "looks more like a Brunnhilde

than a patrician blond Venetian".) When Desdemona realizes that Otello is

safe, we see her literary squirm with joy and relief, photographed in such a

pathetic way that it is downright embarrassing. All those effects

are so striking, so vulgar and cheap that they are almost kitsch by

definition.

The same applies to Zeffirelli's

Aida(s) – always filled with Egyptian and pseudo-Egyptian relics, crowded

to overflowing, always beautiful and always kitschy. Why do there always have

to be a monumental statue of Tut Ankh Amun, giant Ankhs and hieroglyphs?

Because that is what the average European and American operagoer believes to

know about Egypt, what he or she recognizes. And that is where Zeffirelli's

staging ends. The missing authenticity is the hallmark of kitsch.

Zeffirelli's Turandot – a scene

crammed with bric-à-brac, pretty but empty. A fancy cake, drowned in icing. It

might be an interesting experience on one occasion or the other, but who wants a gateau every

time he/she eats? And that's exactly what Zeffirelli wants: He phrased a

normative demand. "That is the way it has to be done" – always and by

everybody, epigonism in the service of "defending Italian culture against criminal

barbarians from the north". Zeffirelli's opera is therefore mummified and

musealized.

Zeffirelli is not an artist. The

effect of his staging is caused by the beautiful costumes and the

bric-à-brac, by a regime of Apollonian beauty, of kitsch and Hollywood pathos.

That is the reason why Zeffirelli is popular in the US, where pathetic

superficiality enjoys great popularity. Zeffirelli says very little by using a

whole arsenal of effects, while art is the opposite: to say much with very

little. Does Zeffirelli respect the composer's will when filling the stage

with meaningless kitsch? Of course not. Turandot in the hands of an

intelligent director is an interesting, unsettling piece of art. In

Zeffirelli's hands it becomes a fancy cake. Briefly:

Zeffirelli's work is large-scale banalisation and stupefies the audience.

Zeffirelli's normative demand is empty because he is himself one of

those who do not respect the composer's will. Or as Vincent Canby of the New

York Times put it: "However sincere his intentions in adapting ‘Otello', Mr.

Zeffirelli less often reveals the original than he ornaments it."

Politics

The talk

about "criminal foreigners" and the defence of Italian culture has of course a

strong political element. Zeffirelli creates groups (we Italians vs. the

criminal foreigners) on a nationalistic base, links everything to culture and

discredits other nations and cultures ("barbarians"). Sure enough, Zeffirelli's

phrases were silly and stupid. And no, Zeffirelli is obviously no intellectual.

That's why it is wrong to name him together with the phalanx of Italian

intellectuals: Visconti, Moravia, Morante, Pasolini, Russo and so on. All of

them were socialists or communists ("di sinistra" anyway) and critical

towards the political system in which they were living – Zeffirelli is a

conservative and a right-wing extremist. He has been a member of Berlusconi's Forza

Italia since 1994 – an antisocial, antidemocratic, ultra-conservative and

(economically) neo-liberal populist party that took power in 1996, going into a

coalition with Gianfranco Fini's Alleanza Nazionale (the party that succeeded

Mussolini's PNF and whose leader Fini frequently praised Mussolini as history's

greatest statesman). Well, Zeffirelli can vote whoever he wants – the problem

is, however, that not only his attacks against foreign colleagues but also his

work is conservative, unprogressive, backward, populist and empty just like the

phrases of his friend Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia.

What is

conservative, populist "art"? Certainly not what Visconti showed in "La terra

trema" or De Sica in "Ladri di biciclette" or Pasolini in "Accattone". It is

no uprising against the political system, against injustice, poverty and social

misery. It is everything but "arte povera". Zeffirelli's work is

commercialised, glossy and much like Berlusconi's clean slate. It's the conservative

façade: always controlled, superior, wealthy, beautiful,

decent, spick and span. That is conservative realism, which in reality is a realistic

deceit, a clever lie that remains on the surface and pretends that

everything is all right. That is not what art is, because it is dishonest,

false and lying. Zeffirelli is either honest and conservative without being

intelligent or he is intelligent and conservative without being honest or he is

honest and intelligent – but then he would not be a conservative.

Art does not

bedazzle, it moves. Zeffirelli's work is the anachronistic glamour of an

aristocratic world that does only exist for the upper class and ignores

all the rest. It is undemocratic and hence carelessly ignores everything a

composer like Puccini for example wanted. Al pueblo, no se desciende, se

asciende.

Conservative

theatre means a theatre that has to stay as it is – or, like in the case of

Zeffirelli, the way that he believes it has been one day. Does he really

believe that this is what Verdi and Puccini wanted? A theatre that does not

renew itself on stage, year after year, that does not remain alive and up to

date? A stage that always looks the same? Too bad that Zeffirelli forgot the

music, which renews itself in every performance: music, opera is a

reproductive art. Within the rules given by the composer, sure enough. But why

does the same not apply for the staging? There is certainly no need to

stage Rigoletto in Planet-of-the-Apes-style (Munich), or to invent a

paedophilic Sharpless (Berlin). But why does every director have to stick to

"old fashioned", "realistic", "traditional" concepts à la Zeffirelli? Both the

Bieitos and the Zeffirellis are wrong, they are extremists on opposite sides, and they

ruin the future of opera.

Epigonism is

not art. Reproductive art cannot live if it's not steadily opened up,

illuminated, aired and watered. And whoever tries to prevent that, fossilizes opera

and ultimately works against it. Like Zeffirelli.

[1] Assmann, Jan: Ägypten in Verdis Aida; in:

Musik & Ästhetik, 6. Jg., Nr. 21 01/2002, p. 12

[2] Arnold, Dieter: Moses und Aida. Das Alte

Ägypten in der Oper, Dauer und Wandel; in: Sonderschriften des Deutschen

Archäologischen Instituts Abt. Kairo 18, 1985, p. 175

[3] Assmann, p. 23

[4] Assmann, p. 10

[5] cf. Hans Werner Henze's Boulevard

solitude (1950/51). Further reading: Henze, Hans Werner: Musik und Politik.

München 1984, p. 368

[6] Rilke, Rainer Maria: Das Stundenbuch; in:

Gesammelte Werke, Bd. 1. Frankfurt a/M 1980, p. 112

[7] Der Brockhaus: Kunst. Leipzig 2001, p.

585

[8] http://cineuropa.org/interview.aspx?lang=en&documentID=35011

[9] http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A0DE5DA163DF931A2575AC0A960948260

[10] ibidem

|

Go Home

|