JOSEPH CALLEJA – THE FALSE MESSIAH

| This article was written in 2008. While the judgements expressed here may have seemed harsh back then, time has proven the author's animadversion basically right, and after a short period in the early 2010s, when Calleja appeared to finally gain control over his unsteady technique, he was finished by the end of the decade, at merely 41 years old. |

When asked about their opinion on the tenor crisis, Joseph Calleja is the answer given by a constantly growing group of connoisseurs. This tenor "has it all", they say, he is a "blast from the past" and reminds of Giacomo Lauri-Volpi in his best days. They stress Calleja's "free voice", his "healthy vibrato", his style, his timbre, the volume of his voice and its carrying capacity and the effortlessness of his singing. Calleja has engagements around the world; he sings in Italy, Germany and in North America, his voice has been heard at Covent Garden, the Vienna State Opera and the Metropolitan Opera. Calleja is young – he just turned 30 this year, he comes from a little island in the Mediterranean, has a chubby likeable appearance, and hence a bit of, well, what we now would call the Paul-Potts-bonus. Already at the age of 19, he gave his debut as Macduff ("Macbeth"), and now his repertoire goes from Arturo ("I puritani") and Edgardo ("Lucia di Lammermoor") to the Duke of Mantova ("Rigoletto"), Verdi's Requiem, Rodolfo (Puccini's "Bohème") and Don José ("Carmen"). In his many recitals, he sings arias by Verdi, Donizetti and Puccini, arias from "I lombardi", "Tosca" and "Turandot", and of course the famous and beloved canzoni and canzonette. Calleja is, judging from his repertory, somewhere between a lyric and a spinto tenor and now finds himself, according to his website, "in excellent company with Luciano Pavarotti, Renata Tebaldi, Joan Sutherland & Renata Tebaldi [sic]." Others even compared Calleja to the great Caruso: "Joseph Calleja's tenor had some of the most authentic Italianate singing produced by a non-Italian I have heard for some time. The Hostias [in Verdi's Requiem] floated gloriously and the Ingemisco used his head voice in a manner that recalled the glory days of Caruso in this music." (E. Dickerson, musicweb-international.com, 2 September 2008). Other analogies go even further: "Vocal drama from a distant era, like we can hear on the old shellac recordings featuring the voices of the greatest of the great: Caruso, Gigli..." (U. Amling in the German newspaper "Der Tagesspiegel", August 2005). Or: "Calleja's voice teacher Paul Asciak mentions 'Anselmi, Bonci, Schipa, early Gigli and Tagliavini'. One could add De Lucia at the further end of the list and Björling at the nearest." (Göran Forsling, "MusicWeb International", November 2005). Calleja is a tenor who sings, "miracle of miracles, in the genuinely bel canto style of another age." (D. Perlmutter, Los Angeles City Beat, 22 June 2006).

In other words, already at the age of 30, Calleja is one of the all time greats, something that very few singers of the past 40 years have achieved. He sings like the great singers we know from the age of the shellac discs. He is the answer to the excruciating tenor crisis.

But first of all, he is a false messiah.

As a singer, Calleja does everything wrong that can be done wrong, and normally, singers who have half of his defects, do not get hired. The worst and most striking defect is his thin, badly produced and poorly supported voice. His voice is so thin that one almost is tempted to say that it is unsuited for operatic singing. His truly guttural voice production does not add favorably. A strong and very fast vibrato is the consequence of these defects, a vibrato, "a flutter some would say but to me that word implies something unsteady, something nervous – and nervous it definitely isn't. Anyway it makes his voice immediately recognizable." (G. Forsling, "MusicWeb International", November 2005) The ignorance of critic Göran Forling is unique: first, he compares Calleja to Björling who had a calm and perfectly produced voice, then he admits that Calleja's voice is fluttering and then he says that the latter is an asset! Another critic describes Calleja as a singer who sings "with the necessary vibrato" (Francesco Mazzotta, "Corriere del Mezzogiorno"), and another one praises the same defect: "He has an interesting individuality of tone, provided by what seems to be a very fast vibrato, which is very appealing." (Alexander Campbell, Classicalsource.com). Now something that has been discussed in the literature on singing, in singing schools and manuals for about 150 years, the defect of a caprino/quick vibrato/flutter, is suddenly a quality feature!

Who writes these things? They are the same people who could not hear that Pavarotti's voice (for example) was not a Verdi voice. The same people who praised Carreras when he strained his voice to death. The reason for their sudden fascination for the faulty vibrato is simple. In our days, vibratos à la Calleja are very much frowned upon – normally. Opera singers who make it do not have such a vibrato. In the "golden age" (the times the critics are referring to, and they mean the time between Caruso and Gigli, about 1910 to 1940), vibratos were more accepted than they are today. Still, they were regarded as defects and rightly so. That is why Franco Corelli got rid of his quick vibrato. Lauri Volpi needed a long time for phasing it out and developed a wobble instead in the last phase of his career. Magda Olivero never really got it under control and that is maybe the reason why she is so commercially under-recorded. Anyway, some critics seem to think that a fast vibrato is a sign of "good, old fashioned" singing, something that they might have heard on some old recording, maybe a record of Merli, Pinza, Franci – and they associate that with the faulty singing of Calleja. They do not hear the difference between a vibrato like Pinza's and the caprino of Calleja. They do not hear that a voice like Pinza's or Merli's (who had relatively quick vibratos), were so well supported, so thick and powerful, and so well controlled that they could create calm moments like in the Otello duet or in Boris Godunov's many monologues without giving a nervous quality to the singing. They do not notice that Pinza's or Merli's vibratos were a means of expression. They do not see that Calleja's much faster vibrato is a sign of a wrong vocal production. The voice is not well supported, it is not free, it is thin and always has that nervous flickering that makes the shaping of long and calm phrases an impossible thing.

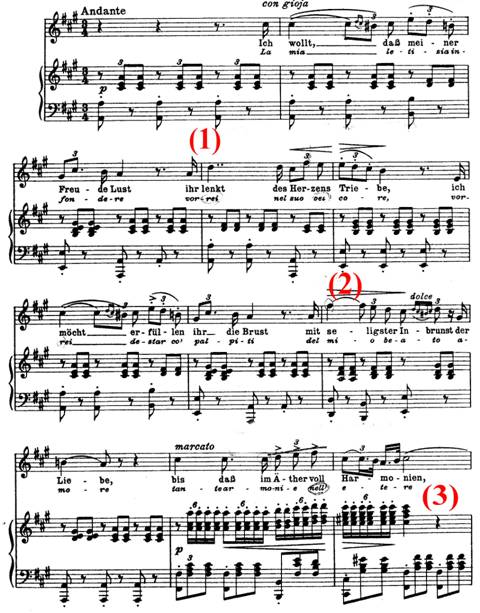

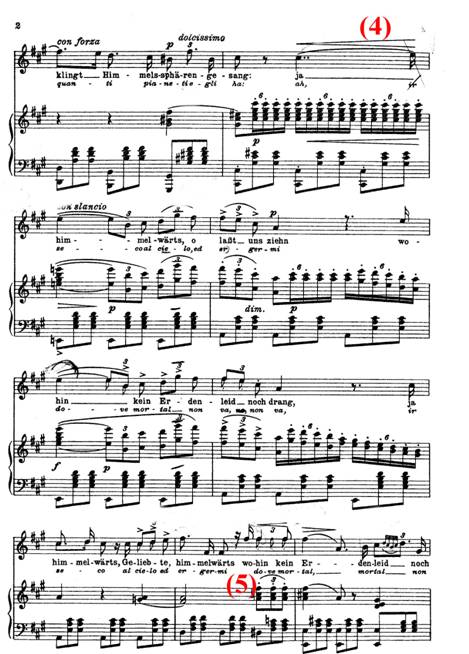

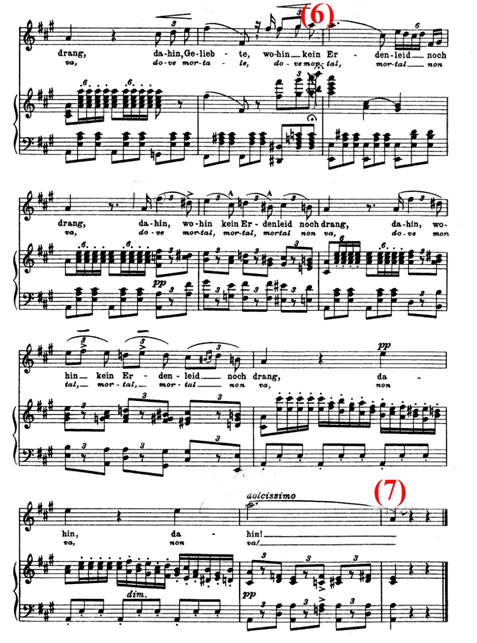

Calleja has great problems with the high register. The high notes are lacking squillo and heft, they are dominated by head voice and seem to have no focus. By the way, what kind of a tenor is Calleja? Is he a lyric tenor or a spinto... or a "remarkably convincing dramatic tenor" (Alan Rich, laweekly.com, 14 June 2006)? He made his debut singing Verdi (Macduff in "Macbeth"), he sang a few belcanto roles (including Edgardo in "Lucia") and some Mozart, then he moved on to light and medium heavy Puccini ("Butterfly", "Rondine" and "Bohème"), some heavy Bizet (Don José) and now he sings Verdi ("Rigoletto", Requiem, "Traviata", "Un giorno di regno" etc.). In recitals he sings show-off pieces like "Granada", the arias from "Tosca" or "Nessun dorma" from "Turandot". Looking at his repertoire, he is neither a lyric tenor nor a dramatic one. His repertoire looks like the one of a spinto tenor. But for a spinto tenor – and now we are coming back to his high register – his top notes are poor. For Verdi, whose music requires a rock solid middle and top register, Calleja is totally unsuited. The same goes for roles like Rodolfo in "La bohème". While Calleja might be OK for act one and two, he lacks the power for the more dramatic act three. Calleja has the timbre of a lirico leggero tenor, a light lyric voice. It is well suited for roles like Almaviva, but not for Verdi – any Verdi. When he tries to tackle the challenges of the Verdi tessitura, he struggles with the middle and top register – like, no, worse than Pavarotti had to struggle. He constricts, the sound is guttural, the vibrato bleats, the sound gets thin: "whisky ed acqua" or, to quote Maria Callas, "diet Coke". Listen to Calleja singing "La mia letizia infondere" from Verdi's "Lombardi" (link below). Already at the beginning, at the word "vorrei" [see score, nr.1], the voice is terribly stuck in two places: the throat and the nose. The /ee/ in "mio" [2] is symptomatic for his entire singing: thin, narrow and constricted. The phrasing is not good; Calleja always seems to be short of air. I have heard him sing "Il mio tesoro" from Mozart's "Don Giovanni" once, and he could not go through the famous long F and the following cadenza without breathing three or four times (McCormack did the whole passage without breathing). Here, he is breathing between "etere" and "quando" although Verdi wrote a bow [3]. He gasps just enough air for singing "quanti", breathes again and then does the same as on [3] between "ah" and "ir seco" – Calleja simply ignores the score and destroys the line [4]. All the notes above F sharp are sitting in the throat and the nose. The consequence is not only a badly produced voice but also that the pronunciation suffers immensely. Not only does Calleja introduce nasal vowels to the Italian language – he also spits the consonants in a totally un-Italian way and puts an /n/ in front of practically every /d/: "nndove" [5]. Then comes an interpolated high B (Verdi did not write that), an Italian tradition. But, alas, the B is thin and poorly focused – if one can't do it properly, why sing it [6]? The text on this note is butchered: "doveaaaa, mortal", whatever this is, Italian it is not. The diminuendo (praised alike by all critics) is insufferable. Here, you hear a thin voice getting even thinner and a vibrato that is nothing but a pure caprino [7]:

Joseph Calleja sings I lombardi alla prima crociata: La mia letizia infondere (Venezia 2006)

When listening to his recital CDs or browsing the web for audio and video clips, one will make a most disturbing discovery: whatever Calleja sings, from "Una furtiva lagrima" to "Nessun dorma" – it all sounds the same. Calleja is, to put it mildly, not a master of characterization. There is only one color on his palette: the thin and unappetizing caprino sound. Calleja ignores the characters he has to portray; his Oronte has the same sound as his Cavaradossi or his Nemorino. Since Nemorino is a better choice for his voice, we would have to say that he sings Puccini and Verdi with a Nemorino voice and expression. That is not enough for a tenor who is the supposed answer to the tenor crisis.

Calleja's defects cannot only be heard, they can easily be seen. That is astonishing as they, in the truest sense of the word, cannot be overseen. How could anybody showing such faults ever go through the mills of competitions and auditions? Calleja's effort (his constriction in the upper body and face in order to compensate for the poor support) can clearly be observed. Here are a few samples; below each picture, you will find the vowel that he sings in that moment:

|  |  |

| Italian I | Italian E | Italian O |

Not often have I seen a singer making such grimaces and snoots like Calleja. When singing, his upper body moves tensed from left to right like a impatient pendulum. The camera of the video these images are taken from had difficulties to capture Calleja. His face is cramped, and he breathes like a fish that is left stranded. Calleja's critic Forsling: "Fernando in La favorita and Nemorino in L'elisir d'amore sound very much like the same person walking in and out of two different operas. [...] A concert might give the same impression but there at least we have the facial expressions to add something to the aural picture." Again, although mentioning Calleja's disability to characterize, Forsling is on the wrong track. Calleja's facial expressions and his gasping do not ameliorate the poor audio impression – on the contrary.

Making faces is a clear sign that the singer is not at ease when singing. The muscular contractions are attempts to regulate and manipulate the sound. But that manipulation is not to be made with the face. When regulating the sound in the face, a faulty production in the sensitive vocal apparatus is evident. These faults have to be fixed and not to be manipulated by constricting and making snoots. Opera is furthermore a multimedial happening which means that you do not only listen but you also look at the singer. Who wants to see a Cavaradossi making grimaces unless he is being tortured (which luckily happens backstage)? Any good school of singing will tell the student to keep a relaxed face and to form the sounds without the aid of facial muscles: sing all the vowels with the same relaxed position, senza cambiare nulla. Do not tense in the upper body. Sure, many famous singers could not live up to these rules. Carreras was always tensed, Pavarotti used to look like he was in great pain when he sang roles that went beyond his possibilities. Nucci regulates the sound with the help of his mouth when singing heavy parts. But that is not the ideal and nothing to imitate. Plus, all of the singers named above had solid, well supported operatic voices – without a caprino. Many good singers sang without strain and without making faces at all. Have a look at Alfredo Kraus, caught singing the same vowels as Calleja above:

|  |  |

| Italian I | Italian E | Italian O |

Kraus' sound production works where it is supposed to work. It is not visible. Kraus can hence use the expressions of his face to enhance the characterization of the roles he performs. In the case of Calleja, the face is busy regulating the faulty sound.

Joseph Calleja is no solution for the tenor crisis – on the contrary. If Calleja's admittedly good material survives the constant ill-usage, Calleja will be active for 30 more years. If the critics continue to approve, Calleja will become a role model, a new Pavarotti and he will influence many generations of young singers who believe that Calleja's thin sound and his caprino are the way to go. Pavarotti had taught that thin voices can sing Verdi, and Calleja will even outclass Pavarotti by singing Verdi with an even thinner voice and an amateurish vibrato. Soon, Calleja will sing roles like Cavaradossi and des Grieux and maybe, he will move on to heavier Verdi repertoire as well. I am sure that we will sooner or later hear him as Radames. Then he will sing Celeste Aida with a caprino diminuendo, and the critics will be enthusiastic and evoke the spirit of the young Lauri-Volpi. But Calleja is not like Lauri-Volpi (or Gigli, Björling, Caruso, Bonci, Schipa, Tagliavini etc.) – he is like Calleja and that means that he is the opposite of Lauri-Volpi, the opposite of the old school tradition that the critics believe to hear. Calleja is one more step towards the Bocellisation of opera, and if he gets the influence that I am afraid he will get, it will be destructive.

The only "miracle of miracles" about Calleja, to quote Ms. Perlmutter once more, is that he is where he is and that he has not been stopped before. Stopping Calleja would have been a good service to the future of opera.

***

ANTIDOTE for Calleja's Lombardi: listen to Gianni Raimondi singing this aria as it should be! Bravo Gianni!